A bitter pill to swallow? Mouth rinsing bitter and salty solutions do not enhance cycling sprint performance

By Dr. Mark Hearris

Research: Post-exercise muscle glycogen synthesis with glucose, galactose, and combined galactose-glucose ingestion by Podlogar et al (2023)

Introduction:

Have you ever experienced the raw, burning sensation at the back of your throat after a shot of tequila? It’s customary to chase tequila with a small dash of salt followed by the sharp, bitter taste of fresh lime, which serve to counteract the initial fiery kick. Now, imagine your legs screaming at you during a maximal sprint effort (for those of you who have ever completed a classic Wingate test, you’ll know what I mean). Akin to how salt and lime quell the burning sensation of tequila shots, researchers in recent years have begun to explore whether such ‘tastants’ could also serve as an effective deterrent to overcome fatigue during strenuous exercise. These include bitter tastes such as quinine (what gives tonic water its bitter taste) and caffeine, as well as hot and spicy tastes such as capsaicin (produced by chilli peppers), which are thought to stimulate an immediate enhancement of maximal/supra-maximal exercise akin to the “fight or flight” response (Best et al., 2021). Based on this rationale, the present study investigated the effects of salty and bitter solutions on maximal sprint cycling performance in a cohort of trained cyclists.

A closer look: How do tastants work?

Although previous studies have demonstrated a performance benefit after rinsing and swallowing unpleasant tastes such as quinine in competitive male cyclists (Gam et al., 2016), the mechanisms by which these exert this effect are unclear. The mouth contains several bitter taste receptors which also extend into the upper gastrointestinal tract and are thought to have the potential to activate the autonomic nervous system (the network of nerves that handle unconscious tasks like breathing and heartbeat) or the recruitment of motor units (by exciting nerve impulses to recruit the muscle fibre to contract) to produce higher levels of power during maximal performance tests (Best et al., 2021). It is also possible that the unpleasant taste of these solutions serve as a distraction from the exercise task and local sensations of “pain” commonly associated with such maximal tests.

The study:

This study used a repeated measures design, where participants (consisting of 12 trained cyclists with an average VO2max of 56.9 ml.kg-1.min-1) took part in four different experimental trials in a randomised order. During each trial, participants were required to perform a maximal 30-second cycling sprint as well as a maximal isometric contraction) of the quadriceps to assess the capacity of the muscle to produce force — think of this as a controlled 1 repetition maximum but solely isolates the muscle group of interest. Immediately before each sprint, participants were given 25 mL of one of four solutions: a) water only, b) a 5.8% salty solution, c) a bitter quinine solution or d) a no solution control, to rinse around their mouth for 10 seconds and then ingest. Importantly, participants were familiarised to these performance measures prior to the main experiment to minimise the influence of “practice effects” which can occur when performing a new test for the first time (e.g. participants performance improves due to practice rather than the specific intervention in question).

Findings:

This study used a repeated measures design, where participants (consisting of 12 trained cyclists with an average VO2max of 56.9 ml.kg-1.min-1) took part in four different experimental trials in a randomised order. During each trial, participants were required to perform a maximal 30-second cycling sprint as well as a maximal isometric contraction) of the quadriceps to assess the capacity of the muscle to produce force — think of this as a controlled 1 repetition maximum but solely isolates the muscle group of interest. Immediately before each sprint, participants were given 25 mL of one of four solutions: a) water only, b) a 5.8% salty solution, c) a bitter quinine solution or d) a no solution control, to rinse around their mouth for 10 seconds and then ingest. Importantly, participants were familiarised to these performance measures prior to the main experiment to minimise the influence of “practice effects” which can occur when performing a new test for the first time (e.g. participants performance improves due to practice rather than the specific intervention in question).

Relevance:

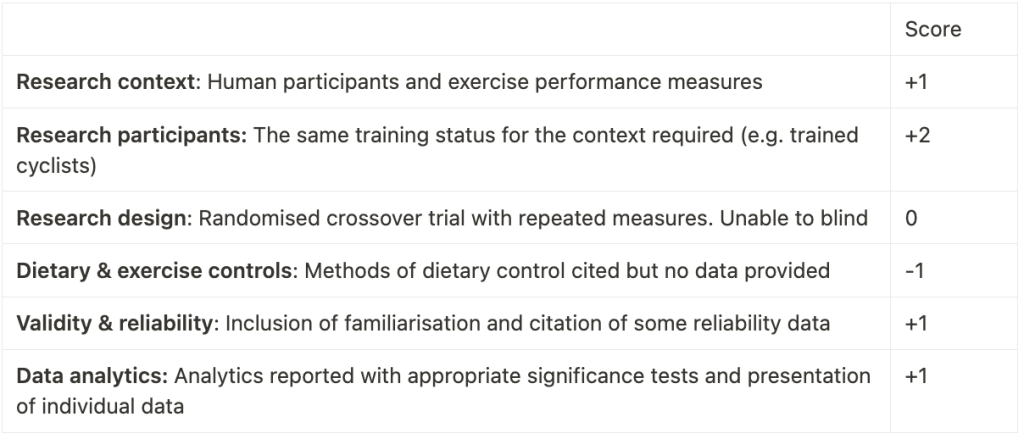

Given the applied research question of this study, it seems only right to assess the adopted research design using the recently published Paper-to-Podium matrix (Close et al., 2019). As can be seen from the table below, the research design scores highly in the majority of assessed components, suggesting these data can be used to guide practitioners’ decisions on the use of such solutions in practice. On this basis, the current evidence suggests that the use of either bitter or salty solutions to enhance maximal sprint cycling performance is unwarranted and may impair performance in some individuals given the large variability in responses. That said, the individual data also show large positive responses (4-5%) in some participants suggesting that some athletes may respond well to this type of intervention and individual testing should be used during training or low-level competitions. Whilst some of the variation may be explained by potential learning effects (despite the use of a familiarisation trial), the high feasibility of implementation and the relatively low risk warrants further investigation on a case-by-case basis, leaving neither stone or shot of tequila left unturned in the pursuit of high performance.

Complement this research with this article:

New insights into enhancing maximal exercise performance through the use of a bitter tastant by Gam et al (2016) open access

References:

Best, R., McDonald, K., Hurst, P., & Pickering, C. (2021, Feb). Can taste be ergogenic? Eur J Nutr, 60(1), 45-54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02274-5

Close, G. L., Kasper, A. M., & Morton, J. P. (2019, Feb). From Paper to Podium: Quantifying the Translational Potential of Performance Nutrition Research. Sports Med, 49(Suppl 1), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-1005-2

Driller, M. W., Argus, C. K., & Shing, C. M. (2013, Jul). The reliability of a 30-s sprint test on the Wattbike cycle ergometer. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 8(4), 379-383. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.8.4.379

Gam, S., Guelfi, K. J., & Fournier, P. A. (2016, Oct). New Insights into Enhancing Maximal Exercise Performance Through the Use of a Bitter Tastant. Sports Med, 46(10), 1385-1390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0522-0